2021 began with a cautious sense of optimism, not least concerning the environment.

In the U.S., President Joe Biden was in, and that other guy was out. While in the UK, even our climate skeptic, rambling prime minister, Boris Johnson, was pushing the importance of sustainability and climate mitigation. (Or at least, he kept saying he was.)

Since then, various politicians have said that they’re just about to get serious on the environment. But while there have been plenty of bold, even inspiring climate promises, very little actual progress has been recorded. In fact, some things have gotten much, much worse.

2022 needs to be about climate change action

The recent COP26 conference—supposedly the moment of truth for the climate—was the zenith of 2021’s all-talk and no action problem. But if 2021 was the year of forward planning for climate change, could 2022 be the year of doing? If world leaders are truly are serious about protecting the planet, it will have to be.

Here’s what needs to happen next to make those promises a reality.

The end of deforestation

The topic of deforestation has been a source of both optimism and horror over the last 12 months, as concerted, often hopeful global efforts to prevent it have failed to make much meaningful difference. (In many areas, deforestation rates are actually increasing.)

One of the first major deals of COP26 saw nearly 120 world leaders pledge to eradicate deforestation by 2030. Meanwhile, Europe is set to ban key imports like coffee and cocoa from companies unable or unwilling to prove their deforestation-free status.

But while increasing acknowledgment of deforestation is undeniably progress, global leaders must act now, and certainly sooner than 2030. They must also stop treating problems like deforestation as a single-issue.

For example, the COP26 deal fails to acknowledge the central role of animal farming (both legal and illegal) in deforestation, while Europe’s ban does not yet include rubber, another key driver. Both measures also fail to act immediately and go too easy on the implicated producers.

Meanwhile, a new report shows how even the fashion industry is contributing to deforestation. Much like the meat, coffee, cocoa, and rubber industries, a lack of supply chain transparency gives suppliers deniability about their own role in environmental destruction.

Ensuring there are appropriate repercussions for companies that continually fail to maintain their own supply chains is essential, and so is moving away from industrialized meat production and other problem products, starting with the wealthy countries who are the worst offenders.

Eliminating our dependence on coal

Fossil fuels are on the way out, and none more so than coal—the single most polluting energy source in the world. But transitioning away from carbon is more complicated than it might seem, and while promises are piling up, nobody in government seems quite sure how to actually make the change. (Though experts insist that it is both necessary and “entirely doable.”)

Countries that have already promised to divest will need to start making measurable efforts in 2022, and Australia’s current administration—notorious for its climate skepticism—desperately needs to take these issues seriously. Some countries have already announced much-needed financial support for others moving forward, but more wealthy nations will need to step up if this is to work (we’re looking at you U.S., China, and Japan).

To move away from fossil fuels, the world needs sustainable energy, so the sooner governments actively facilitate this (both at home and abroad) the better. The renewables market is growing fast, and customers are already enthusiastic about sustainability. The policy should reflect this.

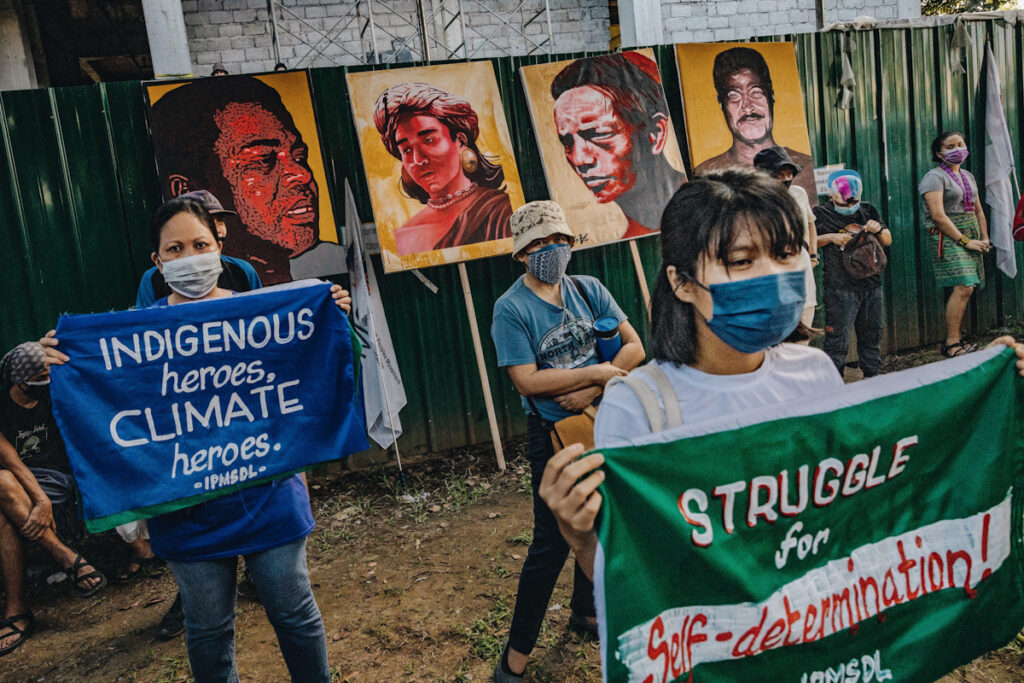

Restore and protect Indigenous land

COP26 claimed to prioritize inclusivity and diversity, but Indigenous representatives overwhelmingly felt tokenized and excluded from talks—if they were able to make it to the event at all. Politicians continue to pay lip service to the power of Indigenous communities, but do (almost) nothing to support them. This is obvious to all, shameful, and must change.

Studies repeatedly show the disproportionate role Indigenous people have in environmental conservation and reforestation. Furthermore, the deplorable global history of racial injustice is forever linked with issues like deforestation and climate change. Moving forward, the governments who have repeatedly ignored these communities must let the solutions come from them directly. This will result in more equitable and more effective environmental action.

Chief Judy Wilson, who attended COP26 as part of the Assembly of First Nations delegation, told CNN: “If you’re not hearing our voices, and we’re not at the table—and we’re not—if you’re not listening to us, then that’s just for show.”

An end to industrialized animal agriculture

COP26 was also roundly criticized for almost entirely ignoring the problem of industrialized animal agriculture. (The closest talks got was a feed additive deal by JBS, the world’s largest and arguably most notorious meat company.) This is despite the fact that multiple nations, IGOs, and NGOs—including the UN and WHO—are championing plant-based and lab-grown meat.

Ditching factory farming and intensive agricultural methods would support everything from better worker safety to consumer health. It would also reduce greenhouse gas emissions, bolster food insecurity, immeasurably improve animal welfare, and even reduce the risk of future pandemics. Ultimately, industrialized agriculture has no future.

Prior to COP26, over 50 global NGOs wrote to Johnson and other hosts expressing concern over animal agriculture’s absence from the conference. They also suggested tried-and-tested solutions such as shifting subsidies from meat and dairy to grains and other crops. The science on factory farming is as clear as it is on fossil fuels, but government action is still lacking.

“Animal agriculture is one of the most significant contributors to climate change,” wrote the signatories. “This is our chance to focus on constructive efforts to reduce deadly emissions from intensive animal agriculture and safeguard our planet for generations to come.”

Promotion and preservation of biodiversity

There has been a lot of talk about the need to improve biodiversity, but once again government and private sector behavior does not reflect the global greenwashing of environmental destruction. (Don’t forget, the taxpayer-funded immolation of Britain’s most valuable carbon store is government-backed and took place in the run-up to COP26.)

As with animal agriculture, there needs to be a total overhaul of land ownership, subsidies, and conservation. In England alone, half of the country is owned by less than one percent of the total population, with many aristocratic families’ land ownership stretching back for generations.

While “stewardship” has a time and a place, some of the most successful conservation projects involve minimal intervention, instead allowing ecosystems to repair, recover, and rewild semi-naturally. So-called protected areas also require more meaningful enforcement, with semi-protected locations (such as some MPAs) continuing to allow hunting and fishing.

Back in June, UNEP released a report that highlighted the urgent need for “more nature,” not just the protection of what we have left. “The conservation of healthy ecosystems – while vitally important – is now not enough,” writes UNEP. “We are using the equivalent of 1.6 Earths to maintain our current way of life, and ecosystems cannot keep up with our demands. Simply put, we need more nature.”

Better electric vehicles

The electric vehicle market is booming, and set to keep growing over the next decade as more companies transition away from traditional combustion engines and towards full or partial electrification. In 2020, despite an overall contraction in car sales, EV sales specifically increased by a huge 67 percent from the year before.

Volvo aims to fully replace fossil fuel vehicles by 2030, while Ford is hoping to be all-electric throughout Europe by the same year. Honda has pledged 100 electric car sales by 2040. Meanwhile, the UK has pledged to ban all new fossil fuel-powered cars, also by 2030.

However, the vast majority of people can’t afford new vehicles at all, let alone modern, electric ones. If governments want to encourage a global transition to EVs, they must again incentivize, support, and otherwise increase people’s access to sustainable vehicles.

Furthermore, experts say that simply replacing the approximately 1.5 billion cars already on the road with electric vehicles won’t solve all our problems. There are still issues of overcrowding, overproduction, and overconsumption. Governments must simultaneously invest in public transport, bicycles, and other even more sustainable means of locomotion.

Stop greenwashing us all

2021 has also seen countless pledges of “net-zero,” with deadlines ranging from 2025 through to 2070. But we need to see an honest reevaluation of what net-zero really means. Otherwise, it’s just greenwashing. It doesn’t mean producing no greenhouse gas emissions, it simply means balancing production with the removal of GHGs from the atmosphere, via carbon offsetting or carbon capture.

We have the technology to transition away from fossil fuels (experts say it’s “entirely doable, and it is doable fast”), so gambling with irreparable damage to the planet and countless human lives for the sake of a few extra years of overconsumption is an extremely low bar.

It also encourages the world to place stock in tech-bros such as Elon Musk and Richard Branson, who played a significant role creating those emissions in the first place. Less production, less consumption, and less emissions are the only way forward.