Joshua Zeman’s obsession with “52,” the so-called loneliest whale in the world, began during a particularly difficult breakup. Something about the whale’s story resonated with him, and Zeman says that from the very first moment he learned about 52, he was “immediately moved.”

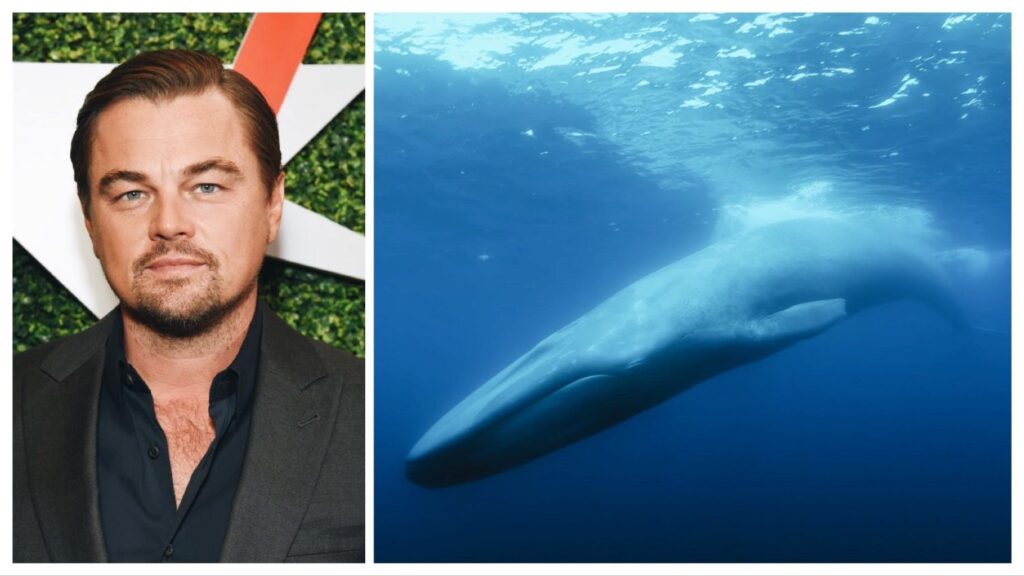

As he dug deeper, he began what he describes as an “Ahabian,” decade-long study of the elusive animal, culminating in the upcoming documentary The Loneliest Whale: The Search For 52 (2021), which is co-produced by actor and environmentalist Leonardo DiCaprio. “The film is about a quest,” explains Zeman. “I think we’re all so caught up in our lives that we don’t go on quests anymore.”

An American producer and director, Zeman is best known for his work on 2004’s Mysterious Skin and 2009’s Cropsey. But for The Loneliest Whale, he worked simultaneously as writer, director, producer, narrator, and co-star, in order to document what became an intense passion project.

“I never would have guessed that making a film about a whale would have made me a better human being,” Zeman says laughing, when asked if looking for the whale really did help him work through his breakup. “I connected with so many people on such a deeper level.”

“That’s the great irony of the story. It’s not necessarily just me and you talking, it’s me and you talking about a whale that suddenly makes you and I that much more connected,” he adds. “I never would have had that experience or those emotional thoughts if it wasn’t for talking about a whale.”

Who is the Loneliest Whale?

The 52-Hertz whale, or just plain 52, is so-called because of his higher-than-average singing voice, recorded at (you guessed it) 52 hertz. That’s just above the lowest register available when playing the tuba, and slightly higher than the deepest note on a double bass.

The majority of other fin and blue whales in the Pacific Ocean sing at approximately 10 to 20 hertz, meaning that 52’s vocalizations are at best peculiar, or at worst unintelligible, to the rest of his species.

While 52’s sex is still technically unconfirmed, singing is overwhelmingly the remit of male whales—possibly used as seduction, communication, or both—making it extremely likely that 52 is, in fact, a male.

Because of his unusual singing, some researchers hypothesize that 52 may have been unable to connect effectively with other whales at all, perhaps spending his long life alone and isolated. This, in part, is how 52 has earned his nickname as the world’s loneliest whale. In turn, that moniker has given 52’s story enduring appeal to those it resonates with, including Zeman.

“The idea of this lonely whale swimming out through the ocean, that’s like our mirror,” he says. “That’s our human existential crisis looking back at us. Because none of us want to die alone, and that’s basically our biggest fear.”

Of course Zeman is not the only human to respond so strongly to 52’s compelling (though almost certainly anthropomorphized) story, which has inspired music, plays, merchandise, and tattoos since going viral in 2004.

This almost universal appeal is what first started the director on his path to making The Loneliest Whale, though he now talks enthusiastically about the hard science behind his search—and whale behavior in general.

This personal development is apparent in the film itself, which sets out to define and demystify the story of 52 once and for all, using all technical and theoretical means at Zeman’s disposal.

Finding One Whale in 63 Million Square Miles of Ocean

Zeman began crowdfunding for the project back in 2015 and managed to get together enough backing to ensure seven days at sea. Just one week to find the elusive 52; a single whale somewhere in the 63 million square miles of the Pacific Ocean.

A team of scientists, biologists, and other experts assembled for the search, including John Hildebrand of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography—who has recorded the 52-hertz whale song on several different occasions—and Oregon-based marine-mammal expert Bruce Mate.

The project gained additional momentum when actor and activist Leonardo DiCaprio donated $50,000 to the film’s Kickstarter, and even signed on to co-produce alongside his Appian Way colleague Jenifer Davisson, Zeman himself, and fellow actor and environmentalist Adrian Grenier.

When Zeman began work on the movie, 52 had not been heard for over 10 years. But during filming, new recordings suddenly placed the whale in the relatively accessible section of the ocean off the southern California coast. The Loneliest Whale combines fresh footage of the crew working, along with archived material and background information on the search so far. It also touches on the dangers facing the ocean and the animals who live within it.

Whaling, entanglement in fishing equipment, global warming, and ship strikes are just some of the biggest threats to cetaceans and other marine life. The Loneliest Whale highlights these, along with noise pollution and other human-caused problems, specifically through their impact on 52 himself.

‘Then This Ship Comes in and Blows the Whole Story Apart’

One of the most striking moments in the film is when Zeman’s team is actually within sight of 52, but are interrupted when a boat from a local shipping route disturbs the whale.

This reframes the impact of ocean noise on whales in a whole new way—disrupting the crew’s (and by extension, the viewer’s) quest when it was so very near to fruition.

“We’re so close to finding 52 and then this ship comes in and blows the whole story apart,” admits Zeman. “[But] if I can’t get you to care about what it [marine noise pollution] does to whales, maybe I can reframe that to how it affected our quest.”

This concept is central to Zeman’s production style, and he explains that he wasn’t setting out to make a run-of-the-mill environmental documentary. Instead, he wanted to produce a film that reflected the impact of 52 on people in a way that could change how the world thinks about whales and the ocean altogether.

If it works, it won’t be the first time such a project has changed global attitudes towards whales. The end of the 1960s saw the large whale population significantly depleted. But after Songs of the Humpback Whale (1970) became the bestselling environmental album ever, people began to see the enormous marine animals in a whole new light, and recordings of their singing sparked renewed advocacy and protest around the world.

“If you care, you can change the world. But how do you get people to care? This lonely whale is a metaphor for us,” says Zeman. “I think it’s a great and interesting way to get us to care about the ocean. […] If you can find ways to connect with people, then they can care.”

How Much Do We Actually Know About the 52-Hertz Whale?

When humans first heard 52, they didn’t even realize he was a whale at all. He was discovered when U.S. Navy-built hydrophones (used to monitor enemy submarines) accidentally picked up the unusual whale song in 1989, and renowned oceanographer and marine mammal researcher Bill Watkins was called in to identify the sound. 52 was then recorded again in 1990, 1991, and once more in 1992.

Watkins spent the following years tracking 52, up until his death in 2004. Shortly before Watkins passed away, he published a paper summarizing his work so far. It was also Watkins who first surmised that 52 was solitary, unique, potentially the first or last of his kind, and unable to find a mate—perhaps failing to bond with other whales at all.

Currently, the leading theory is that 52 is a hybrid; a combination of two different whale species that led to his unique vocalisations. Common whales in this part of the world include the blue, fin, humpback, minke, and sei. 52’s behaviour indicates that he is at least part blue whale, and some researchers (including Watkins) have hypothesized that he is part fin whale, too.

Other experts have questioned whether 52 is one-of-a-kind at all. According to Christopher Willes Clark, who created the 1992 recordings of 52, many different idiosyncratic whale calls have been documented over the years. Plus, even if his species is unique, there may be more than one whale—something supported by Hildebrand’s recordings, often taken hundreds of kilometers apart within just a few hours of each other.

“We still don’t know technically if that’s Bill Watkin’s original whale,” explains Zeman. “John Hildebrand is working off the West Coast on wind farms to gauge their impact on ocean noise pollution. He is also retrieving the data from the rest of his hydrophones to find out whether there are two or more 52-hertz whale hybrids.”

It’s worth noting that, even if his singing is particularly unusual, it doesn’t necessarily mean other whales can’t understand him, and his loneliness remains conjecture by enthusiasts and spectators. “Blue whales, fin whales, and humpback whales: all these whales can hear this guy, they’re not deaf. He’s just odd,” says Clark, as reported by the BBC.

‘This One Story of a Whale Brought Us All Together’

Hopefully it’s not too much of a spoiler to say that the search for 52 does not end here for Zeman and his crew. While the film doesn’t bookend his story conclusively, it does document another chapter in a journey shared by countless individuals over the last 32 years.

Viewers can share the highs and lows of this journey with the crew, most notably when Zeman comes tantalisingly close to the complete truth, or when the documentary highlights the sheer magnitude of the ocean and the whales that traverse it.

According to Zeman, The Loneliest Whale is a story about connection as well as loneliness, never more apparent than in the bonds that unite his team as they search for 52 onscreen.“This one story of a whale brought us all together,” says Zeman.

“This creature is more alone than any of us could ever imagine, and yet refuses to give up, continues to call out, hoping one day to be heard,” he continues. “It is a story that I want to share with others–one that inspires us to have hope and reminds us that the bonds of love, friendship, and family we share must remain meaningful as we navigate the vast oceans of our ever-changing world.”

The Loneliest Whale is coming to theaters on July 9, 2021. It launches to video-on-demand services a week later, on July 16.