At the conclusion of COP26, nearly 200 countries finally adopted an agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and attempt to prevent further, catastrophic global heating.

The now-signed Glasgow Climate Pact aims to preserve the Paris Agreement’s key goal of less than 1.5C warming. It requires wealthy nations to increase climate finance for developing countries, and for big polluters to submit stronger emissions-cutting measures by 2022.

However, this final version of the agreement has been heavily compromised, and COP26 president Alok Sharma was moved almost to tears by the last-minute erosion of crucial details.

Negotiations continued into the weekend, well past the official deadline, and further final adjustments were made on Saturday at the behest of India, China, Iran, and other fossil fuel-dependent nations to weaken the pact’s core stance on eliminating coal.

The original draft was, notably, not particularly strict anyway. It required the acceleration of efforts to “phase out” coal power and other fossil fuel subsidies by an unspecified date. Instead, it now merely requires the “phasing down” of coal, implying that the fossil fuel industry will continue to have a future despite its incompatibility with climate mitigation.

The pact itself is representative of COP26 as a whole, and reactions from the public, activists, experts, and politicians to the talks and promises have been mixed, at best.

7 of the biggest moments from COP26

Despite its seemingly endless disappointments and an underwhelming conclusion, the intentions of COP26 remain pure. (It’s also extremely difficult not to sympathize with Sharma in his role as the world’s least-appreciated babysitter.) Because of this, it’s still possible the Glasgow Pact will facilitate some positive changes in the world, but only time will tell whether leaders’ optimistic promises from the last two weeks will turn into actions.

Over 100 world leaders promise to end deforestation

The promise: On day two of the conference—and in the first major deal of COP26—110 world leaders promised to end deforestation by 2030. Overall, the signatories represent over 85 percent of the world’s forests, and if the pledge is properly acted on this could prove to be a huge moment for climate mitigation and the environment in general. It’s also particularly welcome that the deal acknowledges the role of Indigenous communities in conservation.

The problem: Unfortunately, a similar public-private pledge was facilitated by the UN in 2014 and has spectacularly failed to even slow deforestation over the intervening years. Some have also criticized 2030 as too late a goal, giving governments the best part of a decade to continue cutting down forests. Much like delayed emissions targets, it may be too little too late.

The solution: For one, actually discussing the impact of the meat industry on deforestation will be an integral part of tackling this problem, as beef is the number-one driver of deforestation in the world’s tropical rainforests, including the Amazon.

The number two reason is soy production, the vast majority of which is also used in the raising of food animals. In general, leaders need to actually make hard decisions on land development and other economic “positives” that continue to damage the environment, both at home and abroad.

Indigenous peoples to receive $1.7 billion in recognition of conservation role

The promise: Following the deforestation pact on day two, 12 donor countries have pledged nearly $20 billion of public and private funds to support Indigenous people advance their land rights, specifically in recognition of their disproportionate role in conserving forests. It also came with a promise to include Indigenous and local communities in the decision-making process.

The problem: Official recognition of how Indigenous people’s land rights must be part of conservation is long overdue and extremely welcome. However, COP26 has already failed in its promise of inclusion. Indigenous activists (including representatives from Mexico’s Indigenous Futures collective) faced practical, bureaucratic, and structural obstacles to their participation.

Many others could not make it to Glasgow at all. “Indigenous people are more visible but we’re not taken any more seriously; we’re romanticized and tokenized,” said Eriel Deranger, executive director of Indigenous Climate Action, speaking to the Guardian.

The solution: Recognizing Indigenous peoples’ invaluable role in climate mitigation is one thing, but unless tangible action is taken to make sure these voices are actually heard at events, such public statements will fail to make a difference; as long as meaningful action is not taken, these words mean less than nothing.

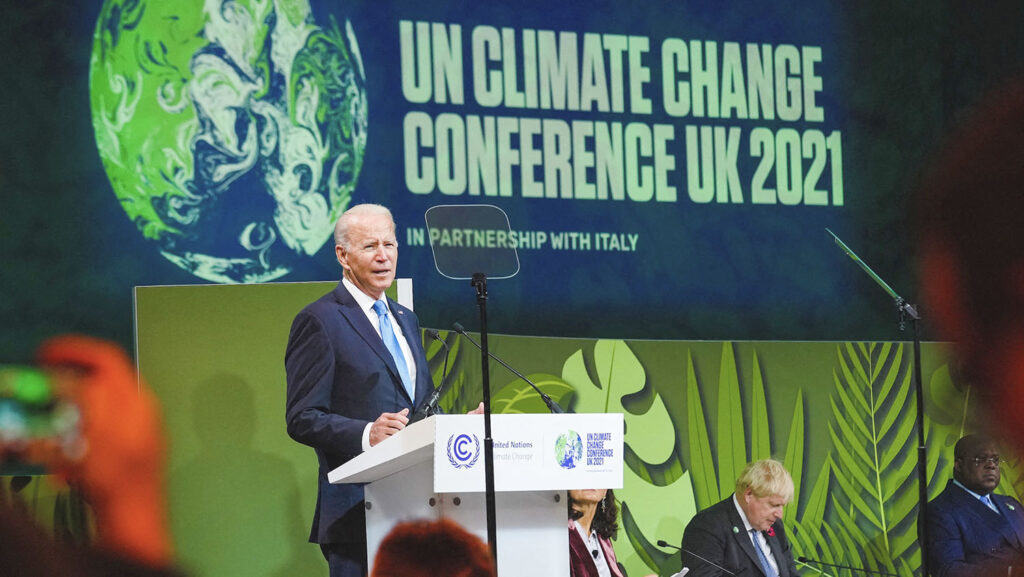

The U.S. spearheads pledge to reduce methane emissions by 2030

The promise: U.S. President Joe Biden announced a groundbreaking Global Methane Pledge at COP26, conceived in partnership with the EU and also signed by an additional 100 countries.

It aims to cut methane emissions worldwide by nearly 30 percent before the end of the decade, and goes hand-in-hand with the EPA pushing oil and gas companies to more accurately detect and repair leaks. Overall, this pledge has the potential to seriously inhibit global warming and make significant positive changes moving forward.

The problem: China, Russia, India, and Iran, four of the top 10 methane emitters, have not joined the agreement. And much like the deforestation pledge, there are no consequences for signatories who fail to meet the agreed-upon reductions. Once again, there was no discussion of the impact of meat on methane emissions, despite the fact that grazing animals like cows are responsible for about 40 percent of the global methane budget.

The solution: Participation from all relevant parties and meaningful consequences (outside of the devastating impact of climate change) would ensure that the pledge actually results in new legislation and policy change for the world’s governments.

India promises net-zero by 2070

The promise: Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a net-zero goal of 2070, a first for the fourth-largest emitter of carbon dioxide in the world. While a full two decades after the generally accepted ideal deadline of 2050, the announcement has been welcomed, in part, as India’s large population has much lower emissions per capita than other major countries. India also set itself a deadline of 2030 to reduce its overall emissions by one billion tons.

The problem: Some critics suggest that 2070 is far too late a deadline for such a pledge, while others highlight the many downsides of net-zero as a concept in general. (Primarily that net-zero does not mean true zero, and allows for further emissions as long as they are offset appropriately.) Similar criticism has been leveled at the planting of new trees to replace old-growth woodland and carbon capture to dull the effects of ‘accepted’ GHG emissions.

The solution: The subtext running throughout COP26 seems to be that while any measures are a step in the right direction, the need for leaders to prioritize continued economic growth is fundamentally incompatible with appropriate climate action.

Bolder pledges are needed, and more concrete roadmaps to carry us there. Modi is correct to demand climate finance from industrialized nations to facilitate India’s transition from fossil fuels, but ultimately this must happen far sooner than 2070 if we are to have any hope of stopping climate change.

More than 40 countries agree to ditch coal

The promise: Representatives from over 40 countries (including major coal users such as Canada, Poland, South Korea, Chile, and Vietnam) have all agreed to move away from fossil fuel over the next 20 years. Signatories also pledged to immediately end all new investment in coal generation, with wealthy nations targeting the 2030s and poorer economies targeting the 2040s. At least 20 participants are publicly committing to phasing out coal for the first time.

The problem: Despite the promising nature of the agreement, some of the world’s biggest coal-dependent countries (including China, India, and the U.S., the three biggest consumers of 2020) did not participate. Furthermore, a hard deadline of 2030 was changed last minute to “as soon as possible thereafter” for major economies. The soft nature of this target (and once again the lack of repercussions for failure) do not bode well for divestment in the coming years.

The solution: As with the previous agreements, a failure to participate on the part of the world’s biggest polluters seriously undermines this pledge’s credibility. While there have been several commitments to providing climate finance, there must be increased efforts from the wealthy (who are also those most responsible for climate change) to support other nations in their transition away from fossil fuels. (Including still unfulfilled commitments dating back to COP15.)

The Pacific ocean is getting a ‘mega-MPA’

The promise: Four Pacific-facing Latin American countries announced that they will be joining their respective marine reserves to create one enormous Marine Protected Area (MPA). Ecuador, Columbia, Panama, and Costa Rica are all signatories on the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor (CMAR) agreement, protecting around 200,000 square miles of important migratory routes for endangered aquatic animals such as sharks and rays.

The problem: This pledge is a significant moment for climate mitigation and environmental protection that has been welcomed by environmental groups and activists.

The main issue here, as with all MPAs, is that they are notoriously difficult to monitor and protect, as shown by existing areas around the world. There are also two different varieties: “no-take” and partially protected. While the former bans all harmful activities, partially protected areas merely provide the illusion of conservation. (Much like “protected” land which continues to allow hunting.)

The solution: As with the majority of mainstream conservation, there is an issue of transparency. MPAs are inarguably a positive step forward, but the exact extent to which they protect aquatic life must be clearly defined. (For example, will the CMAR agreement allow fishing? Industrial vessels? Tourism? Or will it strictly prohibit human interference? If so, how?)

China and the U.S. will work together to ‘enhance climate action’

The promise: During the second week of COP26, China and the U.S. announced that they would be working together to “enhance climate action” in the coming years. The two countries are the world’s two largest CO2 emitters, and their international relationship has been strained for some time. The partnership has been cautiously welcomed worldwide.

The problem: While the UN and the EU welcomed this step as an encouraging moment for international collaboration and climate mitigation, activists once again pointed out the lack of concrete commitments and action to go with the vaguely optimistic sentiment.

The solution: Climate Action Tracker currently rates China’s policies, actions, and domestic targets as insufficient, and its fair share target highly insufficient. Meanwhile, the U.S.’s policies, actions, and fair share targets are insufficient, and its climate finance contributions are critically insufficient. Both countries urgently need to do more to cut emissions and support renewables.

‘We cannot solve a crisis with the same methods that got us into it’

Overall, highlights of COP26 include some of the most significant climate pledges ever, while low points—from the ominous presence of Big Oil to repeated, blatant hypocrisy from world leaders themselves—signified business as usual for the coming years.

The British government has been attempting to frame the event as a success from day one, but it notably excluded several key topics almost entirely, including animal agriculture (a widely acknowledged key driver of global warming), and electronic waste (an already huge and growing problem).

Furthermore, the lack of representation for many of those most impacted by climate change (specifically Indigenous activists) and the continued persecution of environmental protestors (including a nighttime raid on COP26 visitors without alternative food or shelter) highlights the inability of the political establishment to think laterally about these issues and those they impact.

Some see these oversights as a reflection of the conference’s outright (and perhaps inevitable) failure. Even the most significant pledges lack concrete details, and the final announcement of the Glasgow Climate Pact follows a report by Climate Action Tracker highlighting the huge disparity between governments’ PR and their actions.

The world is currently on target for at least 2.4C warming, but possibly as much as 2.7C if government policies do not improve in the coming years. The organization specifically cites the conference’s “massive credibility, action and commitment gap” for these shocking figures.

“It is not a secret that COP26 is a failure. It should be obvious that we cannot solve a crisis with the same methods that got us into it in the first place,” said activist Greta Thunberg, while speaking at a rally organized by Fridays For Future Scotland. “We need immediate drastic annual emission cuts unlike anything the world has ever seen.”

The vast majority of the world’s people believe that the climate crisis is a global emergency and want real commitments from their leaders. Now is the time for action, not more greenwashing. For more of our coverage of COP26, read on here.